The original lating text presented in "Library of Foreign Writers about Russia. Volume 1 (1836)" and can be found here: https://archive.org/details/01003824818/page/n555/mode/2up_

The original text doesn't contain chapters or sections (except for the introduction), so we are presenting it as is.

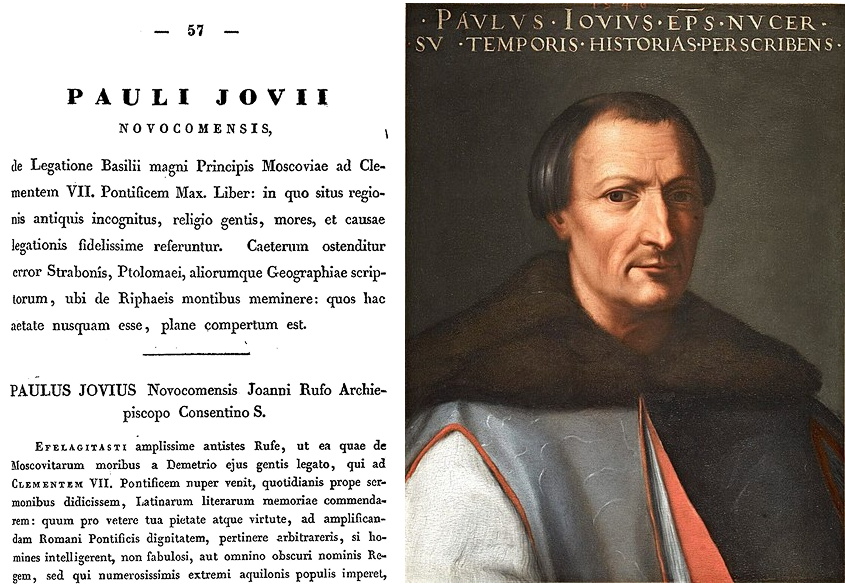

PAULI JOVII NOVOCOMENSIS,

"On the Embassy of Basil, Grand Prince of Muscovy, to Pope Clement VII": A book in which the location of a region unknown to the ancients, the religion of the people, their customs, and the reasons for the embassy are most faithfully recounted. Moreover, it is shown that the error of Strabo, Ptolemy, and other geographical writers regarding the Riphaean Mountains—mentioned by them but now clearly proven not to exist in our age—is corrected.

Paul Jovius of Como to John Rufus, Archbishop of Cosenza, Greetings:

Most reverend Bishop Rufus, you urged me to record in Latin the customs I learned from Demetrius, the envoy of the Muscovites, who recently came to Pope Clement VII, through nearly daily conversations. With your longstanding piety and virtue, you thought it would enhance the dignity of the Roman Pontiff if people understood that a king—not a mythical or obscure figure, but one ruling numerous peoples of the far north—desired, at a most opportune time, to unite with us in religion and form a perpetual alliance. This comes when some German tribes, once seen as excelling in piety, have defected from us and even from the gods themselves in a mad and wicked rebellion. Though I could rightfully have declined this task, being occupied with weightier studies, I have undertaken it with eagerness and speed to honor your request, lest delay or excessive refinement diminish its freshness. By this alone, my longstanding devotion to you and my willingness to serve are clearly shown—preferring a loss of honor, if any is to be hoped from this modest talent, over thwarting your most noble wish. Farewell.

The region’s location, little known to Pliny, Strabo, and Ptolemy, will first be briefly described and depicted in a printed map. Then, imitating Tacitus—who separated a book on German customs from his continuous histories—we will narrate the people’s customs, wealth, religion, and military practices with a concise style, using nearly the same simplicity with which Demetrius himself explained them to us in leisure, prompted by curious and gentle inquiry. For Demetrius uses Latin competently, having learned its rudiments in Livonia from a young age and visited many Christian provinces while serving in notable embassies. After proving his reliability and diligence as an envoy to the kings of Sweden and Denmark and the Grand Master of Prussia, he last resided at Emperor Maximilian’s court, where, amidst a throng of all sorts, he refined any barbarity in his calm and docile nature with elegant manners. The reason for this embassy was provided by Paul Centurio, a Genoese, who, arriving in Muscovy for trade with letters of recommendation from Pope Leo X, voluntarily discussed uniting the rites of both Churches with Basil’s confidants.

For Paul, with a bold and boundless mind, sought a new and incredible route to obtain spices from India. He had learned through rumor, while trading in Syria, Egypt, and Pontus, that spices could be brought up the Indus River from distant India, then carried overland across the Paropamisus Mountains’ ridges to the Oxus River in Bactria. Rising from nearly the same mountains as the Indus, the Oxus flows into the Hyrcanian Sea, carrying many rivers to the port of Strava. From Strava, he saw an easy voyage to the market of Cytracham at the Volga’s mouth, then upstream via the Volga, Oka, and Moskva rivers to the city of Moskva. From Moskva, he argued, one could travel overland to Riga and the Sarmatic Sea, reaching all western regions easily. He was fiercely angered beyond measure by the Portuguese, who, having conquered much of India and seized all its markets, bought up spices, shipped them to Spain, and sold them across Europe at higher prices and with exorbitant profit. They guarded the Indian Ocean’s shores with constant fleets, halting trade routes through the Persian Gulf, up the Euphrates, across the Arabian Sea’s narrows, and down the Nile to our sea—routes that once abundantly supplied Asia and Europe at lower cost. Worse, he claimed, the Portuguese’s distant voyages and fetid holds corrupted the spices, their potency, flavor, and aroma fading in Lisbon’s warehouses, leaving only stale remnants for sale, while fresher stocks were hoarded.

Though Paul argued bitterly to all, stirring great envy against the Portuguese and asserting that royal revenues would grow if this route opened—since Muscovites, who used vast amounts of spices, could sell them cheaper—he achieved nothing regarding that trade. Basil deemed it unwise to open regions near the Caspian Sea and Persian realms to an unknown foreigner. Thus, thwarted in all his hopes, Paul turned from merchant to envoy, bearing Basil’s letters—Leo X now dead—to Pope Hadrian, expressing great goodwill toward the Roman Pontiff with many honorable words. A few years earlier, during a war with Poland and the Lateran Council, Basil had requested safe passage for his envoys to Rome through John, King of Denmark, father of Christian II (recently deposed). But that same day, both King John and Pope Julius died, disrupting the plan, and Basil abandoned the embassy.

Soon after, war broke out between him and Sigismund, King of Poland. When the Pole won a notable victory at the Borysthenes, Rome decreed thanksgivings as if Christian enemies had been defeated, greatly alienating Basil and his people from the Roman Pontiff. When Hadrian VI died, leaving Paul—already preparing a second journey—unsupported, Clement VII succeeded him and sent Paul, still dreaming of an eastern route, back to Muscovy with letters. These urged Basil with warmest encouragement to recognize the Roman Church’s majesty and form a lasting religious alliance, which the Pope promised would be most beneficial and honorable. The Pope seemed to pledge that, with sacred pontifical authority, he would name Basil king with royal insignia if he rejected Greek doctrines and joined the Roman Church. Basil sought the title of king by pontifical grant, deeming it a sacred right and mark of papal majesty, knowing even emperors traditionally received the golden crown and scepter from popes. It was said he had sought this from Emperor Maximilian through several embassies.

Thus Paul, more skilled in swift travel than in profit from his youth, though old and afflicted with chronic strangury, reached Moskva quickly and was kindly received by Basil. He stayed two months at his court, but, daunted by exhaustion and the vast journey’s difficulty, abandoned his wild Indian trade dreams. With Demetrius as envoy, he returned to Rome sooner than we expected. The Pope received Demetrius in the grandest part of the Vatican, with gilded ceilings, silk beds, and exquisite tapestries, ordering him clad in silk robes. He assigned Francis Chiericati, Bishop of Teramo—experienced in distant embassies and known to Demetrius from Paul’s tales—as his guide in divine and civic matters.

After resting a few days and shedding the grime of his long, arduous journey, Demetrius, in splendid native attire, was led to the Pope, humbly paid respects per custom, and offered sable pelts in his and his king’s name. Basil’s letters were then presented, translated into Latin by Demetrius and later Nicholas of Sessa from Illyricum, as follows:

To Clement, Pope, shepherd and teacher of the Roman Church, from Basil, by God’s grace Emperor and ruler of all Russia, and Grand Duke of Vladimir, Muscovy, Novgorod, Pskov, Smolensk, Tver, Yugra, Perm, Vyatka, Bulgaria, etc., Lord and Grand Prince of Lower Novgorod, Chernigov, Ryazan, Volhynia, Rzhev, Bely, Rostov, Yaroslavl, Beloozero, Udoria, Obdoria, Kondinia, etc.:

You sent us Paul Centurio, a Genoese citizen, with letters urging us to join you and other Christian princes in counsel and strength against the enemies of the Christian name, ensuring safe and open passage for our and your envoys to learn of each other’s welfare and affairs through mutual friendship. We, with God’s good and fortunate aid, have stood resolutely against the impious foes of Christianity thus far and resolve to do so henceforth. We are also ready to agree with other Christian princes and provide peaceful routes. For this, we send Demetrius Erasmus, our man, with this letter, and return Paul Centurio. Send Demetrius back swiftly, ensuring his safety to our borders. We will do the same if you send your envoy with him, so that through speech and letters we may be better informed of matters, and, understanding all Christians’ intentions, adopt the best plans. Given in our Lord, in our city of Muscovy, in the year 7033 from the world’s beginning, April 3.

Demetrius, highly skilled in human and especially sacred matters, seems to bear secret instructions on great affairs, which we hope he’ll soon reveal in private talks. Recovering from a fever caused by the climate change, he regained his strength and ruddy complexion. At sixty, he joyfully attended the Pope’s rites honoring Saints Cosmas and Damian—solemn with music—and joined the Senate when Cardinal Campeggio returned from Pannonia, welcomed by the Pope and court. He also marveled at the city’s holy temples, Roman grandeur’s ruins, and ancient works’ lamentable remains. We believe he’ll soon depart for Muscovy with the Pope’s envoy, the Bishop of Skara, and worthy gifts.

The name “Muscovy” is recent, though Lucan mentions the Moschi as kin to Sarmatians, and Pliny places them near the Phasis River’s sources above the Euxine Sea to the east. Their region spans vast borders—from Alexander the Great’s altars near the Tanais’s sources to the earth’s ends and the Boreal Ocean, almost under the North Star. Mostly flat and fertile for grazing, it’s swampy in summer. Fed by great, frequent rivers, it floods when winter snows melt under the sun, turning fields into marshes and fouling paths with water and mud until new frost freezes rivers and swamps, paving roads with solid ice for carts.

The Hercynian Forest covers only part of Muscovy and is dotted with settlements. Long human labor has thinned it, so it’s not the impenetrable, dense wilderness many imagine. Yet it teems with huge beasts, stretching unbroken from Muscovy’s east to north toward the Scythian Ocean, its vastness ever eluding explorers. Near Prussia, massive, fierce bison-like bulls—called Bisontes—are found, along with elk-like Alces with trunks, tall legs, and no knee joints—known as Lozzi to Muscovites, Helenes to Germans, noted by Julius Caesar. Also, enormous bears and large, fearsome black wolves roam.

To the east, Muscovy borders the Scythians, now called Tartars—a wandering, warlike people famed through ages. Tartars use covered wagons as homes, hence the ancient name Hamaxobii. Their vast camps, not fortified by ditches or wood but by countless mounted archers, replace cities. Divided into Hordes—congregations like cities in their tongue—each is led by emperors chosen by lineage or valor. They often war with neighbors and fiercely vie for power. Their hordes are nearly numberless, stretching to Cathay, a famed eastern city by the ocean, across vast wastes.

Those nearest Muscovites are known for trade and frequent raids. In Europe, near Achilles’ Run in Tauric Chersonese, the Praecopitae—whose prince’s daughter wed Selim, the Turks’ emperor—plague Poland, ravaging between the Borysthenes and Tanais. Allied with Turks in faith and custom, they hold Caffa, a Genoese colony once called Theodosia, in Taurica. Tartars between the Tanais and Volga in Asia obey Basil, sometimes choosing their emperor by his judgment. Among them, the Cremii, once mighty in wealth and war, lost all power to internal strife years ago. Beyond the Volga, the Casanii loyally befriend Muscovites, claiming client status. Further north, the Sciabani thrive with herds and numbers. Beyond them, the Nogai now hold supreme wealth and martial fame, their vast horde ruled not by an emperor but by a council of wise and brave elders, like Venice’s Republic.

Beyond the Nogai, slightly south toward the Hyrcanian Sea, the noble Zagathai Tartars inhabit stone-built towns, including Samarcand—a city of vast size and renown, split by the Jaxartes, Sogdiana’s great river, which flows 100 miles to the Caspian. In our age, Ismail Sophus, Persia’s king, fought them with mixed success, losing Armenia and his capital, Tauris, to Selim in one battle, distracted by their threat. Samarcand birthed Tamburlanes—or Themircuthlu, as Demetrius corrects—who defeated Ottoman Bayezid, Selim’s great-grandfather, at Angora in Galatia, dragging him in an iron cage through Asia in triumph after a terrible victory. Much silk cloth comes from this region to Muscovites.

Inland Tartars offer only swift horse herds and fine, unthreaded wool felts, ideal for rainproof cloaks. Muscovites trade them wool tunics and silver coins, as Tartars scorn bodily adornment or excess goods, content with a felt cloak against harsh skies and relying on arrows to fend off foes. Yet, when raiding Europe, their princes lately bought iron helmets, breastplates, and curved swords from Persians.

To the south, Muscovy’s borders are hemmed by Tartars above the Maeotian Swamp in Asia and around the Borysthenes and Tanais in Europe, across plains sloping to the Hercynian Forest. Roxolani, Getae, and Bastarnae once dwelt there, likely birthing the name Russia—Lithuania’s lower part is called Russia, while Muscovy is White Russia. Lithuania faces Muscovy from the northwest; to the west, inland Prussia and Livonia abut it, where the Sarmatic Sea curves north in a crescent from Cimbrian Chersonese’s narrows.

At the ocean’s far shore, where Norway and Sweden—vast realms—join by an isthmus, live the Laplanders, a people unimaginably wild, wary, and fleeing at any foreign step or sail. Knowing neither crops, fruits, nor nature’s bounty, they hunt with arrows for food and wear varied beast hides. Their homes are leaf-filled caves or hollow trees, carved by fire or rot. Some fish by the sea with crude but effective skill, smoking catches like crops. Short, sallow, and swift-footed, their vast numbers elude even nearby Muscovites, who deem small attacks mad and large ones neither useful nor glorious. They trade pure white ermine pelts with merchants, avoiding all contact—leaving skins in open spots, dealing with absent strangers in utmost trust.

Beyond, between northwest and north in perpetual gloom, some credible witnesses report Pygmies—grown to barely a ten-year-old’s height, timid, chattering like apes, far from human stature or sense. Northward, countless peoples under Muscovite rule stretch three months to the Scythian Ocean. Closest is Colmogora, rich in grain, split by the Dividna—greatest of northern rivers, named for a lesser stream to the Baltic. Like the Nile, it floods unpredictably, not seasonally, with fat silt resisting the sky’s algae, fierce northern blasts, and snow-fed swells. Its vast channel flows to the ocean through unknown tribes like a sea, unpassable in a day’s rowing. As waters recede, fertile isles remain. Wheat grows without plows, sprouting and ripening fast as nature hastens before the river’s next flood.

The Juga River joins the Dividna; at their confluence lies Ustjuga, a famed market 600 miles from Moskva. Permii, Pecerri, Inugri, Ugolici, and Pinnagi bring precious marten, sable, deer-wolf, and black-and-white fox pelts, trading for varied goods. Permii and Pecerri supply sables—light, gray-furred, prized for princes’ robes and matrons’ collars—received from remoter ocean tribes. Once idol-worshipping pagans, they now honor Christ. Beyond, rugged mountains—perhaps ancient Hyperboreans—yield noble falcons: white, speckled Herodium; Hierofalchi, ardea foes; and sacred peregrines, unknown to ancient princes’ hunts.

Further, tribute-paying peoples yield to unknown nations, uncharted by Muscovites—no one reaching the ocean, only rumors and merchants’ tales heard. Yet it’s certain the Dividna, drawing countless streams, rushes north to a vast sea. Sailing its right coast to Cathay—unless land intervenes—seems plausible. Cathay lies at the east’s edge, near Thrace’s parallel, known to Portuguese in India via Sinae and Malacca to the Golden Chersonese, bringing sable garments—suggesting Cathay’s nearness to Scythian shores.

When we asked Demetrius if any memory of Goths—who overthrew Rome and its emperors 1,000 years ago—lingered in tales or records, he said the Goths and King Totila’s name shine brightly. Many joined that campaign, including Muscovites, with Livonians and Tartars, called Goths because Goths from Iceland or Scandavia led it.

These borders enclose Muscovites, whom Ptolemy called Modocas, now named—surely—from the Moskva River, which also names their royal city. Moskva, the realm’s brightest star, sits centrally, famed for rivers, dense homes, and a mighty citadel. Stretching oblong along the Moskva’s bank for five miles, its wooden houses—split into dining, cooking, and sleeping areas—are spacious, neither ornate nor low. Huge Hercynian beams, squared and pegged at right angles, form sturdy walls with little cost or delay. Most homes have vegetable and pleasure gardens, swelling the city’s vast circuit. Each district has chapels; a grand temple to the Virgin Mother, built 60 years ago by Aristotle of Bologna—master of wonders and machines—rises prominently. At the city’s head, the Neglina River, driving grain mills, joins the Moskva, forming a peninsula tipped by a citadel of stunning Italian design, with towers and ramparts.

Below, fields teem with deer and hares, huntable only by Basil’s intimates or envoys with his indulgence. Two rivers feed three city quarters; a wide moat, fed by them, guards the rest. The Jausa River fortifies another side, joining the Moskva just below. Flowing south, the Moskva meets the grander Oka near Kolomna; soon after, the swollen Oka joins the Volga, where Lower Novgorod—a colony of the greater city—sits at their confluence.

The Volga, once Rha, rises from vast White Lakes north-northwest of Moskva. Like Alps birthing the Rhine, Po, and Rhone, these swamps—no mountains found despite much travel—spawn the Dividna, Oka, Moskva, Volga, Tanais, and Borysthenes. Tartars call the Volga Edil, Tanais Don; the Borysthenes is now Neper, flowing to the Euxine below Taurica. The Tanais feeds the Maeotian Swamp near Azov’s famed market. The Volga, leaving Moskva south, winds east, west, then south, crashing into the Hyrcanian Sea. Above its mouth lies Cytracham, a Tartar city of Median, Armenian, and Persian trade.

Across the Volga, Casanum names the Casanii Horde, 500 miles from the Caspian. Upstream, 150 miles from the Sura River’s mouth, Basil founded Surcicum as a safe haven with inns for merchants and travelers reporting Tartar unrest to border chiefs. Muscovite emperors shifted capitals by need or whim. Novgorod, facing northwest toward Livonia’s sea, was once the realm’s head—vast in buildings, blessed by a huge, fish-rich lake, and a 400-year-old temple to Saint Sophia, rivaling Byzantine emperors’ works. Its near-eternal winter and long nights, with the Arctic pole 64 degrees above the horizon—six more than Moskva—bring endless summer heat from short nights.

Vladimir, 200+ miles east of Moskva, also bore the royal name, moved there by bold emperors to counter Scythian raids with nearby troops, sitting on the Klyazma River before the Volga. Yet Moskva, for its gifts, is deemed worthiest—centrally placed, fortified by citadel and rivers, its preeminence unchallenged by any age or rival city. It’s 500 miles from Novgorod; midway, Ottoferia straddles the Volga, still small near its source, flowing through woods and plains. From Novgorod to Riga, the Sarmatic coast’s nearest port, is just under 500 miles—a smoother route with frequent villages and Pskov, hugged by two rivers. From Riga, seat of Livonia’s Grand Master, to Lübeck in Germany’s Cimbrian gulf is 1,000+ perilous sea miles.

From Rome to Moskva is 2,600 miles by the shortest route: through Ravenna, Treviso, the Carnic Alps, Noricum’s towns, Vienna in Pannonia, past the Danube to Olomouc in Moravia, then Cracow in Poland (1,100 miles); 500 from Cracow to Vilnius, Lithuania’s capital; and 600 from Vilnius via Smolensk beyond the Borysthenes to Moskva. Winter speeds this last leg over snow and ice with sleds; summer swamps slow it unless bridged with endless labor.

Muscovy yields no vines, olives, or sweeter fruits—only melons and cherries—as tender plants wither under icy northern blasts. Yet fields bear wheat, rye, millet, panic, and legumes. The surest harvest is wax and honey from abundant bees, nesting not in man-made hives but tree hollows, forming noble swarms on branches. Vast honey pools fill ancient trees, often unsearched in deep woods.

Demetrius, witty and genial, told a laughable tale: a neighbor farmer, seeking honey, leapt into a huge hollow tree, sank chest-deep in a honey flood, and lived on it two days, his cries unheard in the wild. Near death, he grabbed a bear’s hindquarters as it dipped for honey, startling it to leap out with him, saving him by chance. Muscovites export fine flax, hemp ropes, ox hides, and huge wax blocks across Europe. No gold, silver, or base metals save iron, nor gems, are found—nature’s slight offset by noble pelts, whose value soars with human greed, fetching thousands of gold coins per garment. Once cheaper, northern tribes, ignorant of luxury, traded them for trifles; Permii and Pecerri gave sables for an iron axe’s worth pulled through its handle-hole.

Five hundred years ago, Muscovites worshipped pagan gods—Jove, Mars, Saturn, and others crafted by ancient folly. First Christianized then, they adopted Greek rites as Greek bishops split from the Latin Church, following them with deep faith. They hold the Holy Spirit, third in the Trinity, proceeds only from the Father—though truth says from Father and Son. This dispute, debated at Florence under Pope Eugene IV, ended with Greeks admitting, after clear proof, the Spirit comes from the Father through the Son, a verbal rather than doctrinal fault.

They make the sacrament not from unleavened bread, as we rightly do, but leavened, sharing both bread and wine—like our priests—with all, a grave error Bohemians followed, defecting from the Latin Church in our fathers’ time. Strangely, they believe no priestly aid or loved ones’ piety helps the dead, denying purgatory—where souls, purged by fire, kin’s rites, and papal indulgence, reach heavenly bliss. In other rites, they mimic Greeks, arrogantly rejecting Rome’s primacy. They abhor Jews, barring them as vile and wicked, claiming they taught Turks to cast bronze cannons.

The Gospels’ tale of Christ’s life and miracles, and Paul’s epistles, are loudly read from platforms during rites; virtuous priests recite Church doctors’ homilies publicly, even outside services. They shun hooded preachers who harangue crowds with lofty mysteries, believing simple doctrine, not arcane interpretations, best guides the unlearned to virtue. These sacred texts, plus Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory, are kept in Illyrican translations. Bishops and minor priests oversee cities and villages, settling disputes and punishing vice with stern authority.

Their chief priest, the Metropolitan, comes from Constantinople’s Patriarch; archimandrites and bishops are chosen by lot from top candidates. Two monastic orders exist: one freer, like our Franciscan or Dominican followers; the other, Saint Basil’s stricter rule, confines holier monks to cloisters, never leaving, living harshly in hidden sanctums, famed for tamed flesh and firm faith.

All fast four times yearly, often for days, avoiding meat, eggs, and milk: in spring after Ash Wednesday, like us; midsummer for Peter and Paul; early fall for the Virgin’s Assumption; and winter for Christ’s Advent. Wednesdays exclude meat, Fridays eggs and milk, but Saturdays brim with lavish feasts. Unlike us, they skip vigil fasts. They revere temples, barring the impure unless bathed, often leaving some outside during rites, mocked by youths for fresh lapses.

On John the Baptist’s nativity and the Magi’s Easter, priests share blessed bread bits, thought to ease fever. Other rites occur on frozen rivers: a tabernacle rises, nobles sing hymns, and priests purify flowing water with splashes, opening ice to bless it. Sick leap in, believing sacred waters cleanse disease. The dead, like ours, are borne with modest pomp and veiled heads by priests, buried not in churches—an impious corruption with us—but in outer temple yards, mourned 40 days as we do, odd given their purgatory denial. Otherwise, they steadfastly share our beliefs.

Muscovites use Illyrican language and script, like Slavs, Dalmatians, Bohemians, Poles, and Lithuanians—deemed the widest tongue, familiar in Constantinople’s Ottoman court and Egypt’s Mamluk circles. Saints Jerome and Cyril translated vast sacred works into it. They keep native annals, tales of Alexander, Roman emperors, Antony, and Cleopatra in this script, but ignore philosophy, astronomy, and medicine, relying on herb-wise healers. Years start not from Christ’s birth but the world’s, beginning in September, not January.

Laws, simple and just, crafted by princes and wise men, benefit all, untwisted by lawyers. Thieves, assassins, and bandits face death; some felons endure cold water torture or finger-crushing to confess—a torment deemed unbearable. Youth train in martial games: racing, wrestling, horse-speed, with prizes, especially for archers.

Muscovites are middling height, sturdy, broad, with gray eyes, long beards, short legs, and bellies, riding with bent knees, expertly loosing arrows even in retreat. At home, they eat richly, not elegantly—tables abound with cheap delicacies. Hens and ducks sell for mere silver coins; vast herds yield meat preserved in winter ice for months. Hunting and hawking bring nobler fare—dogs and nets snare beasts, Pocerra’s falcons and hawks take pheasants, ducks, swans, and cranes.

Hawks, lowliest eagles, and falcons—noble ancient hawks—thrive. A black bird with white brows, goose-sized, tastier than pheasant—called Tethter in Muscovite, Erythratio by Pliny—is known to Alpine folk, especially Rhaetians near the Inn’s source. The Volga yields huge, tasty fish, especially sturgeon—ancient Siluri—kept fresh in winter ice. Countless fish swarm White Lakes. Lacking native wine, they import it for feasts and rites; sweet Cretan wine, prized for medicine or princely show, amazes—unspoiled after crossing Cadiz’s straits and stormy seas to Scythian snows.

Commoners drink mead—honey boiled with hops, aged in barrels for nobility—and beer or ale, like Germans and Poles, brewed from wheat, barley, or oats, passed round feasts, said to intoxicate like wine. Summer chills mead and beer with ice from nobles’ cellars. Some relish tart cherry juice, mimicking wine’s warmth and flavor.

Women and wives lack honor other nations grant, treated near as maids. Notable men guard their steps and chastity zealously, barring them from feasts, distant temples, or public outings. Yet common women easily yield to foreigners for little, noble men caring little for such loves. Basil lost his father John 20 years ago. John wed Sophia, daughter of Thomas Palaeologus—Morea’s ruler and Constantinople’s emperor’s brother—exiled to Rome after Turkish conquest. She bore five: Basil, George, Demetrius, Simeon, and Andrew. Demetrius and Simeon died young; Basil wed Salomonia, daughter of George Soborov, a loyal, wise counselor, her virtues marred only by barrenness.

When choosing brides, Muscovites survey all realm’s virgins, summoning the fairest and finest. Trusted men and matrons inspect them—even intimately—until one suits the prince, named worthy of royal vows amid parents’ hopes. Others, vying in beauty and virtue, often wed nobles or soldiers that day. Low-born girls, as princes spurn royal lineage—like Ottoman Turks—rise to the throne’s peak by beauty’s favor.

Basil, nearing 47, excels in form, virtue, subjects’ love, and deeds, surpassing forebears. For six years, he warred with Livonia’s 72 allied cities, winning with few terms given, not taken. Early in his reign, he crushed Poland, capturing and chaining their leader Constantine to Moskva. Later, Constantine, freed, bested him at the Borysthenes above Orsha, yet Smolensk—once Muscovite—stayed Basil’s after Poland’s great win. Against Tartars, especially European Praecopitae, Muscovites often fought successfully, avenging sudden raids.

Basil leads over 150,000 cavalry in banner-divided squadrons, each following its chief. The royal standard bears Joshua, the Hebrew who, per sacred tales, won a long day from God by halting the sun. Foot soldiers are near useless in vast wastes—soil too loose, foes favoring speed over static combat. Their horses, below average height, are tough and swift. Riders wield lances, iron arrows, and rare curved swords, shielded by round Asiatic or angled Greek shields, pyramid helmets, and breastplates. Basil added mounted arquebusiers; Italian-crafted cannons on carts guard Moskva’s citadel.

He dines publicly with nobles and envoys in grand yet untainted regal style, vast silver gleaming on tables. No praetorian guard—only kin—protects him; city folk keep watch. Each district locks gates and bars; none roam at night without light. His court comprises vassals and picked soldiers, rotating monthly from regions to serve and ennoble him. When war looms, armies form from veterans and provincial levies—city prefects draft fit youths, paid modest stipends in peace from local treasuries. Those who truly serve as soldiers enjoy exemption from taxes and are superior to other civilians, and through royal favor, they are powerful in all matters. Indeed, a noble place falls to true valor when war is waged; for by an excellent and in every aspect of administration beneficial principle, each person attains the fortune of either lasting reward or eternal disgrace according to their own distinguished deed.

The latin text can be found in a separate article: Pauli Jovii de Legatione Basilii magni Principis Moscoviae ad Clementem VII