The authentic text of Stepan Bandera's autobiography "My Biographical Data", written by him at the request of friends - members of the OUN in April 1959. The account is brought up to January 1940.

Page 1

Stepan Bandera, April 1959

My Life Data

I was born on January 1, 1909, in the village of Uhryniv Staryi, Kalush County, in Galicia, which at that time belonged to the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, along with two other western Ukrainian regions: Bukovyna and Transcarpathia.

My father, Andriy Bandera, a Greek Catholic priest, was at that time the parish priest in Uhryniv Staryi (the parish also included the neighboring village of Berezhnytsia Shliakhetska). My father was from Stryi. He was the son of townspeople-farmers Mykhailo Bandera and Rozaliya, whose maiden name was Biletska. My mother, Myroslava Bandera, came from an old priestly family. She was the daughter of the Greek Catholic priest from Uhryniv Staryi, Volodymyr Glodzinskyi, and Kateryna, née Kushlyk.

I was the second child of my parents. My older sister was Marta. My younger siblings were Oleksandr, sister Volodymyra, brother Vasyl, sister Oksana, brother Bohdan, and the youngest sister, Myroslava, who died in infancy.

I spent my childhood years in Uhryniv Staryi, in the home of my parents and grandparents, growing up in an atmosphere of Ukrainian patriotism and active national-cultural, political, and social interests. Our home had a large library, and it was often visited by active participants in Ukrainian national life in Galicia, as well as relatives and their acquaintances. Among them were my uncles: Pavlo Glodzinskyi—one of the founders of "Maslosoyuz" and "Silskyi Hospodar" (Ukrainian agricultural cooperatives), Yaroslav Vesolovsky—a member of the Viennese Parliament, the sculptor M. Havrylko, and others.

During the First World War, as a child and teenager, I experienced the war front passing through my native village four times, in 1914–15 and again in 1917, with heavy two-week battles in 1917. The Austro-Russian front moved through Uhryniv, and our home was partially destroyed by artillery fire. That same summer of 1917, we witnessed the manifestations of revolution in the army of Tsarist Russia, the national-revolutionary movements, and the stark contrast between Ukrainian and Russian military units.

Page 2

In October-November 1918, as a boy of not yet ten years old, I witnessed the stirring events of the revival and establishment of the Ukrainian state. My father was among the organizers of the state coup in Kalush County (together with Dr. Kurivets), and I saw him forming military units from the surrounding villages' peasants, armed with weapons hidden in 1917. From November 1918 onward, our family life was marked by the events of building Ukrainian statehood and the war in defense of independence. My father was a deputy in the parliament of the Western Ukrainian National Republic—the Ukrainian National Council in Stanyslaviv—and actively participated in shaping state life in the Kalush region. A particularly significant influence on the formation of my national-political consciousness was the grand celebrations and widespread enthusiasm surrounding the unification of the Western Ukrainian National Republic with the Ukrainian National Republic into a single state in January 1919.

In May 1919, Poland deployed General Haller’s army in its war against the Ukrainian state. This army had been formed and armed by the Entente powers with the intended purpose of fighting Bolshevik Moscow. Under its superiority, the front began moving eastward. Along with the retreat of the Ukrainian Galician Army, our entire family moved eastward, settling in Yaholnytsia near Chortkiv, where we stayed. There, we lived with my uncle (my mother’s brother), Father Antonovych, who was the parish priest in the village. In Yaholnytsia, we experienced both anxious and joyful moments during the great battle known as the Chortkiv Offensive, which pushed the Polish forces westward. However, due to a lack of military supplies, the Ukrainian army’s offensive stalled. Another retreat began, this time beyond the Zbruch River. All the men in my family, including my father, who served as a military chaplain in the ranks of the UGA, crossed the Zbruch in mid-July 1919. The women and children remained in Yaholnytsia, where they endured the arrival of Polish occupation forces. In September of that year, my mother returned with the children to our home village of Uhryniv Staryi.

My father went through the entire history of the UGA in "Greater Ukraine" (that is, on the Dnipro side) during 1919-1920, fighting against both Bolshevik and White Russian forces, as well as surviving typhus.

Page 3

He returned to Galicia in the summer of 1920. At first, he went into hiding from the Polish authorities due to the persecution of Ukrainian political figures. In the autumn of that same year, my father resumed his previous position as parish priest in Uhryniv Staryi.

In the spring of 1922, my mother passed away from throat tuberculosis. My father remained as the parish priest in Uhryniv Staryi until 1933. That year, he was transferred to the parish in Volia Zaderevetska, Dolyna County, and later to the village of Trostianets, also in the Dolyna region (after my arrest had already taken place).

In September or October 1919, I traveled to Stryi, where, after passing the entrance exam, I enrolled in the Ukrainian gymnasium. I had never attended primary school, as the school in my village—like in many other villages in Galicia—had been closed since 1914 due to the teacher being conscripted into the army and other wartime circumstances. My primary education was obtained at home, together with my sisters and brothers, with irregular assistance from home tutors.

The Ukrainian gymnasium in Stryi was initially organized and maintained through the efforts of the Ukrainian community, and later it received official status as a public state gymnasium. Around 1925, the Polish state authorities revoked its independence, converting it into Ukrainian sections within the local Polish state gymnasium. The Ukrainian gymnasium in Stryi followed a classical curriculum. I completed all eight grades there from 1919 to 1927, achieving good academic results. In 1927, I passed my matriculation exam.

My ability to study at the gymnasium was made possible because my father’s parents, who owned a farm in the same city, provided me with housing and support. My sisters and brothers also lived there while attending school. During the summer and holiday breaks, we spent time at our family home in Uhryniv Staryi, which was about 80 kilometers from Stryi. During the holidays at my father’s home and during the school year at my grandfather’s, I worked on the farm in my free time. Additionally, starting from the fourth gymnasium grade, I tutored other students, earning money to cover my personal expenses.

Page 4

Education and upbringing at the Ukrainian gymnasium in Stryi followed the curriculum and was supervised by the Polish school authorities. However, some teachers managed to instill Ukrainian patriotic values within the mandatory system. Nonetheless, the primary source of national-patriotic upbringing for young people came from youth organizations at school. The most prominent legal organizations in Stryi were: Plast, a Ukrainian scouting organization and "Sokil", a sports and gymnastics society. Additionally, there were secret circles of an underground organization among high school students, ideologically linked to the Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO). This underground group aimed to train selected cadres in a national-revolutionary spirit, influence the broader youth community in this direction, and involve older students in auxiliary activities for the revolutionary underground. These activities included fundraising for the maintenance of the secret Ukrainian university, distributing underground and Polish-banned Ukrainian publications from abroad, and resisting efforts to break national solidarity (such as boycotting Polish organizations, conscription, and early elections).

I joined Plast in the third gymnasium class (since 1922) in Stryi, becoming a member of the 5th Plast troop named after Prince Yaroslav Osmomysl. After completing my studies, I joined the 2nd troop of senior Plast members, "Red Viburnum Detachment," until Plast was banned by the Polish government in 1930. (My earlier attempts to join Plast in the first and second classes were unsuccessful due to rheumatic joint disease, which I had suffered from since early childhood. At times, I could not walk and, in 1922, spent about two months in a hospital due to water swelling in my knee). I became a member of the Underground Organization of High School Students in the fourth gymnasium class and was part of the leadership unit of the Stryi gymnasium branch.

After graduating from the gymnasium and passing the maturity exam in mid-1927, I attempted to travel to Poděbrady in Czechoslovakia to study at the Ukrainian Academy of Economics. However, this plan fell through as I was unable to obtain a passport to leave the country. That same year, I remained at my family home, engaged in agricultural work and cultural-educational activities in my native village. I worked at the "Prosvita" reading hall, led an amateur theater group and a choir, founded a gymnastics society called "Luh," and was one of the founders of a cooperative.

Page 5

At the same time, I carried out organizational and training work within the underground UVO in the surrounding villages.

In September 1928, I moved to Lviv and enrolled in the agronomy department of the Higher Polytechnic School. Studies in this department lasted eight semesters: the first two years in Lviv, and in the last two years, most lectures, seminars, and laboratory work took place in Dubliany near Lviv, where the agronomy facilities of the Lviv Polytechnic were located. Graduates, in addition to taking regular exams during their studies, had to pass a diploma exam to receive the title of engineer-agronomist. According to the study plan, I completed all eight semesters between 1928-29 and 1931-32, finalizing the last two semesters in 1932-33. My studies officially ended after completing the required eight semesters, but I was unable to take the diploma exam due to my political activities and subsequent imprisonment. From autumn 1928 to mid-1930, I lived in Lviv, then spent two years in Dubliany before returning to Lviv in 1932-34. During holidays, I stayed in my father's village.

During my student years, I actively participated in organized Ukrainian national life. I was a member of the Ukrainian Polytechnic Students' Society "Osnova" and served on the board of the Agronomy Students' Circle. For some time, I worked at the office of the "Silskyi Hospodar" society, which was engaged in improving agriculture in Western Ukrainian lands. In the field of cultural and educational work, I collaborated with the "Prosvita" society, traveling to nearby villages in Lvivshchyna on weekends and holidays to give lectures and assist in organizing various events. Regarding youth and sports organizations, I was particularly active in Plast, as a member of the 2nd senior Plast troop "Zahin Chervona Kalyna", as well as in the Ukrainian Student Sports Club (USSK). For some time, I was also involved in the "Sokil-Batko" and "Luh" societies in Lviv. My athletic activities included running, swimming, skiing, and basketball, but above all, I was passionate about traveling. In my free time, I enjoyed playing chess, singing in a choir, and playing the guitar and mandolin. I did not smoke or drink alcohol.

Page 6

During my student years, I devoted most of my time and energy to revolutionary and national-liberation activities. This involvement increasingly captivated me, pushing even the completion of my studies into the background. Growing up in an atmosphere of Ukrainian patriotism and the struggle for Ukraine’s independence, I sought and established contact with the Ukrainian underground national-liberation movement as early as my gymnasium years. At that time, this movement was being organized and led in the Western Ukrainian lands by the Revolutionary Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO). I became acquainted with its ideas and activities partly through family connections and even more so through my work in the underground Organization of Secondary School Students. In the upper grades of gymnasium, I began carrying out auxiliary tasks for the UVO, such as distributing its slogans, underground publications, and serving as a liaison. I formally became a UVO member in 1928, initially assigned to the intelligence department and later to the propaganda department. At the same time, I was part of a student group of Ukrainian nationalist youth, which maintained close ties with the UVO. When the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) was founded in early 1929, I immediately became a member. That same year, I participated in the First OUN Conference of the Stryi District.

My responsibilities within the OUN included general organizational work in the Kalush region and membership activities within student cells. At the same time, I performed various functions in the propaganda department. In 1930, I managed the distribution department for underground publications in Western Ukrainian lands. Later, this was expanded to include the technical-publishing department, and at the beginning of 1931, I also took charge of the department responsible for the delivery of underground publications from abroad. That same year (1931), I assumed leadership of the entire propaganda division within the OUN’s Regional Executive, which was then headed by Ivan Habrusevych (who perished in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Oranienburg near Berlin in 1944). In 1932-33, I also served as deputy regional leader, and in mid-1933, I was appointed as the regional leader of the OUN and regional commander of the UVO in Western Ukrainian lands. (Both of these positions were merged in mid-1932 after the Prague Conference in July, which finalized the unification process between the UVO and the OUN. As a result, the UVO ceased to exist as an independent organization and was transformed into the military and combat department of the OUN).

Page 7

I maintained contact with the foreign authorities of the UVO and OUN from 1931, due to the organizational functions I performed, traveling abroad several times via various conspiratorial routes. In July 1932, along with several other delegates from the Regional Executive of the OUN in ZUZ, I participated in the OUN Conference in Prague (the so-called Vienna Conference, which was the most important OUN gathering after the founding congress). In 1933, broader conferences were also held in Berlin and Danzig, which I also attended. Additionally, at smaller conferences and meetings, I had the opportunity several times to discuss the revolutionary-liberation activities of the Organization with the Leader of the UVO-OUN, the late Colonel Yevhen Konovalets, and his closest collaborators.

The revolutionary-liberation activities in ZUZ during my leadership continued primarily along the previous directions, with a stronger emphasis on certain areas and the weakening of others, adjusted to the situation and the development of the liberation movement. The following points can be particularly noted:

a) A wide expansion of membership cadres and organizational networks across the entire ZUZ territory under Poland. Special attention was paid to covering the Northwestern Lands and areas penetrated by communist activities. An action was also launched among Ukrainians living on Polish lands, especially in larger cities. Since before, the organizational work was mainly focused on former military personnel and student youth, now it was carried out among all social strata, with particular attention to the countryside and the working class.

b) A systematic training program for cadres at all organizational levels was established. Three main types of training were set up: ideological-political, military-combat, and underground practice training (conspiracy, intelligence, communication, etc.).

c) In addition to the political, propaganda, and combat activities of the Organization itself, a new form of work—mass actions—was launched, in which broad segments of society actively participated, acting on the initiative, guidance, and ideological leadership of organizational cadres.

Page 8

In this plan, the following actions were carried out: an anti-monopoly campaign (boycott of products from the state tobacco and alcohol monopoly) aimed at creating a moral-political effect; a school campaign against the Polish denationalization policy at that time and in defense of Ukrainian schooling and national education;

d) Alongside the revolutionary activities against Poland, as the occupier and oppressor of the Western Ukrainian Lands, a second front in the anti-Bolshevik struggle was established, equally significant and active in ZUZ (not only OSUZ). This front was directed against the diplomatic representatives of the USSR in ZUZ (the assassination attempt by M. Lemyk on the secretary and political leader of the Soviet consulate in Lviv, Maiilov, and the political trial), against Bolshevik agents, the Communist Party, and Soviet sympathizers. The aim of these actions was to manifest the unity of the liberation front, solidarity of Western Ukraine with the anti-Bolshevik struggle of Central and Eastern Ukraine, and to eliminate communist and Soviet-influenced work among the Ukrainian population in Western Ukraine.

e) In combat activities, expropriation actions previously carried out against Polish state institutions were neglected, and more emphasis was placed on combat actions against national-political repression and police terror by Polish authorities against Ukrainians.

This period of my activities ended with my imprisonment in June 1934. Prior to this, I had been arrested several times by the Polish police in connection with various UVO and OUN actions, for example, at the end of 1928 in Kalush and Stanisławów for organizing the November celebrations—manifestations marking the 10th anniversary of November 1st and the creation of the ZUNR in 1918. In early 1932, I was detained while illegally crossing the Polish-Czech border and spent 3 months in an investigative prison that year in connection with the assassination attempt on Polish Commissioner Chekhowski, and so on. After my arrest in June 1934, I was interrogated in the prisons of Lviv, Kraków, and Warsaw until the end of 1935. At the end of that year and the beginning of 1936, a trial took place before the district court in Warsaw, where, together with 11 other accused, I was sentenced for membership in the OUN and for organizing the assassination attempt on the Polish Minister Bronisław Pieracki, the Minister of the Interior of Poland (who was responsible for leading Poland's extermination policy against Ukrainians).

Page 9

In the Warsaw trial, I was sentenced to death, which was commuted to life imprisonment based on an amnesty law approved by the Polish Sejm during our trial. In the summer of 1936, the second major OUN trial took place in Lviv. I was tried as the regional leader of the OUN for the entire activity of the OUN-UVO during that period. On the defendants' bench were more members of the regional executive that I headed. The verdict in the Lviv trial was merged with the Warsaw trial—life imprisonment. After that, I was held in prisons such as “Święty Krzyż” near Kielce, in Wronki near Poznań, and in Brest on the Bug until mid-September 1939. I spent five and a quarter years in the harshest prisons in Poland, most of which were spent in strict isolation. During this time, I went on 3 hunger strikes lasting 9, 13, and 16 days, one of them together with other Ukrainian political prisoners, and two individually, in Lviv and Brest. I only learned about the Organization's preparations for my escape, which was the subject of the trial, once I was free.

The German-Polish war in September 1939 found me in Brest on the Bug. From the first day of the war, the city was bombed by German aircraft. On September 13, when the position of Polish forces in that area became critical due to the enemy's air operations, the prison administration and guards hastily evacuated, and I, along with other prisoners, including Ukrainian nationalists, gained freedom. (I was freed by nationalist prisoners who somehow learned that I was being held in strict isolation).

With a group of several released Ukrainian nationalists, I headed southwest from Brest towards Lviv. We took side roads, far from the main routes, trying to avoid encounters with both Polish and German forces. We received help from the Ukrainian population. In Volhynia and Galicia, starting from the Kovel region, we connected with the active OUN organizational network, which began forming partisan units, taking care to protect the Ukrainian population, preparing weapons and other military supplies for the future struggle.

Page 10

In Sokal I met with the leading members of the OUN of that area. Some of them were free, others had returned from prison. I discussed the situation with them and the directions for further work. This was the time when the collapse of Poland was already obvious, and it became known that the Bolsheviks would occupy most of the Western Ukrainian lands based on the agreement with Nazi Germany. Therefore, all OUN activities in the Western Ukrainian lands had to be quickly shifted to a single anti-Bolshevik front and adapted to the new conditions. From Sokal, I went to Lviv with Dmitro Maiivskyi-Taras, a future member of the OUN Leadership Bureau. We arrived in Lviv a few days after the Bolshevik army and occupation authorities entered the city.

I stayed in Lviv for two weeks. I lived secretly, but due to the initial disorganization of the Bolshevik police apparatus, I had considerable freedom of movement and made contact not only with the leading activists of the OUN but also with some prominent figures of Ukrainian church and national-church life. Together with members of the Regional Executive and other leading members who were in Lviv at that time, we made plans for the further activities of the OUN in Ukrainian lands and its anti-Bolshevik struggle. The first priority was: building the OUN network and activities in all areas of Ukraine that found themselves under Bolshevik control; the plan for a broad revolutionary struggle with the spreading of the war over Ukrainian territory, regardless of the course of the war; counteraction in case of the mass destruction of Ukraine, regardless of the course of the war; counteraction in case of the mass destruction by the Bolsheviks of the national active forces in the Western Ukrainian lands.

I initially planned to stay in Ukraine and work directly in the revolutionary-liberation activities of the OUN. However, other members of the Organization insisted that I leave the Bolshevik-occupied territories and carry out organizational work abroad. Ultimately, this matter was decided by the arrival of a courier from the Leadership from abroad with the same request. In the second half of October 1939, I left Lviv and together with my brother Vasyl, who had returned to Lviv from the Polish concentration camp in Bereza Kartuzka, and four other members, we crossed the Soviet-German demarcation line using secondary roads; partly on foot, partly by train, we arrived in Krakow.

Page 11

Krakow became, at that time, the center of Ukrainian political, cultural-educational, and public life on the western outskirts of the Ukrainian lands, outside the Bolshevik occupation but under German military occupation and amid gatherings of Ukrainian émigrants in Poland. In Krakow, I joined the work of the local OUN center, where many leading members from Western Ukraine and Polish prisons had gathered; there were also several leading members who had been living earlier in Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Austria. In November 1939, I went for two weeks to the region of Pishchany (Pěšany) in Slovakia for treatment of rheumatism, together with two or three dozen Ukrainian political prisoners released from Polish jails. Among them were many prominent leaders of the nationalist movement in Western Ukraine. Several other leading OUN members, who had been active in organizational work in Western Ukraine, Transcarpathia, and in emigration, also arrived in Pishchany. This made it possible to hold a series of meetings of the leading OUN activists, where the situation, the development of the liberation struggle up to that point, and the internal organizational matters in the region and abroad were analyzed. During these meetings, several important issues for the future struggle of the OUN were crystallized, which required resolution.

From Slovakia, I went to Vienna, where there was also an important OUN station abroad, which had concentrated the OUN's connections with Western Ukraine in the last years of Polish occupation, as well as with Transcarpathian Ukraine. At the end of 1939, or in the first days of 1940, the OUN leader for the Ukrainian lands, Tymchiy-Lopatynsky, also arrived in Vienna. It was decided that we would both go to Italy for a meeting with the then head of the Ukrainian Nationalist Leadership, Colonel A. Melnyk. My trip to him had been planned earlier in Krakow. As a result of organizational meetings in Lviv, Krakow, Pishchany, and Vienna, I became the spokesperson for the leading OUN activists in Ukraine, the activists released from prisons, and the foreign activists who had emerged from the regional struggle of the last years and remained in close contact with the homeland. I was to clarify several issues, projects, and demands of an internal organizational and political nature for the head of the Organization’s Leadership to establish healthy relations between the PUO and the regional revolutionary active members.

Page 12

After the death of the founder and leader of the OUN, Colonel E. Konovalets, abnormal relations of tension and disagreement developed between the Regional Leadership and the active members of the Organization, as well as the PUO. The cause of this was, on one hand, distrust towards some individuals, particularly close collaborators of Colonel A. Melnyk, such as Yaroslav Baranovsky. This distrust grew based on various facts related to his work and organizational life. On the other hand, the regional active members became increasingly wary of the foreign leadership's policy. In particular, after the so-called Vienna Agreement regarding Transcarpathian Ukraine, this turned into an opposition stance against the orientation towards Nazi Germany. The Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact and the political agreement between Berlin and Moscow at the beginning of the war gave this disagreement a political sharpness. The arrival of the regional leader of the OUN made the trip to Colonel A. Melnyk a priority. Together with Tymchiy-Lopatynsky, we had a unified stance on all the fundamental issues of the revolutionary-liberation movement, which was ultimately shared by the general regional active members. We hoped to jointly convince Colonel A. Melnyk and eliminate the growing disagreements.

I went to Italy first, in the first half of January 1940. I was in Rome, where the OUN station was led by Professor E. Onatsky. There I met, among others, my brother Oleksandr, who had been living in Rome since 1933-34, studying there and earning a doctorate in political-economic sciences, getting married, and working in our local station. I had a meeting and conversation with Colonel A. Melnyk in one of the cities in northern Italy, primarily with the regional leader, Tymchiy-Lopatynsky.

These conversations ended with a negative result. Since the previous disagreements mostly concerned the collaborators of A. Melnyk, they inevitably turned against him in light of his position. Colonel Melnyk did not agree to remove Y. Baranovsky from the key position in the PUO, which gave him decisive influence and a detailed insight into the most important matters of the Organization, including regional issues and connections between the homeland and abroad. He also rejected our demand to separate the planning of the revolutionary-liberation anti-Bolshevik struggle from Germany and not to tie it to German military plans.

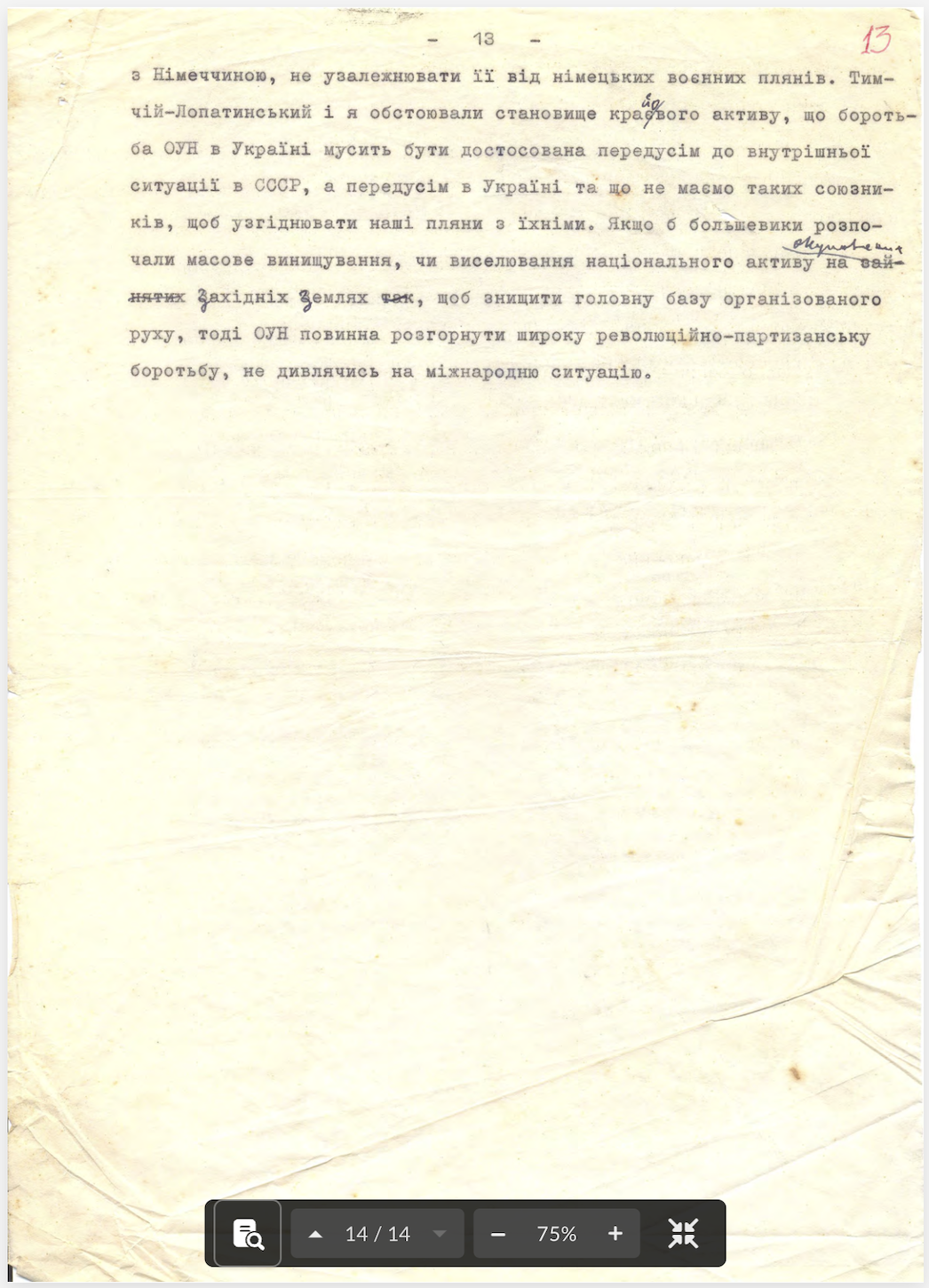

Page 13

Tymchiy-Lopatynsky and I defended the position of the regional active members that the OUN's struggle in Ukraine must be primarily adapted to the internal situation in the USSR, and especially in Ukraine, and that we do not have such allies to align our plans with theirs. If the Bolsheviks started a mass extermination or deportation of the national active members in the occupied western lands to destroy the main base of the organized movement, then the OUN should launch a broad revolutionary-partisan struggle, regardless of the international situation.

Source: All pages from the OUN Archive